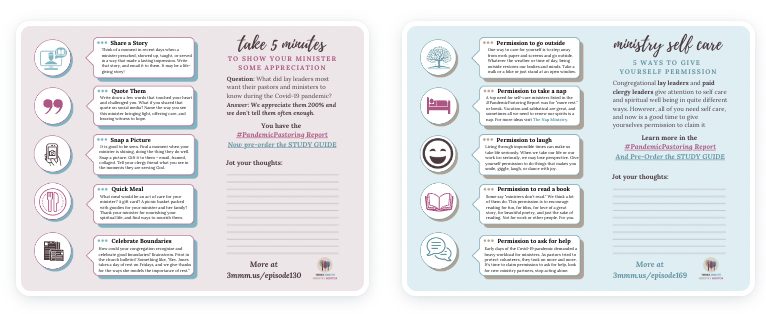

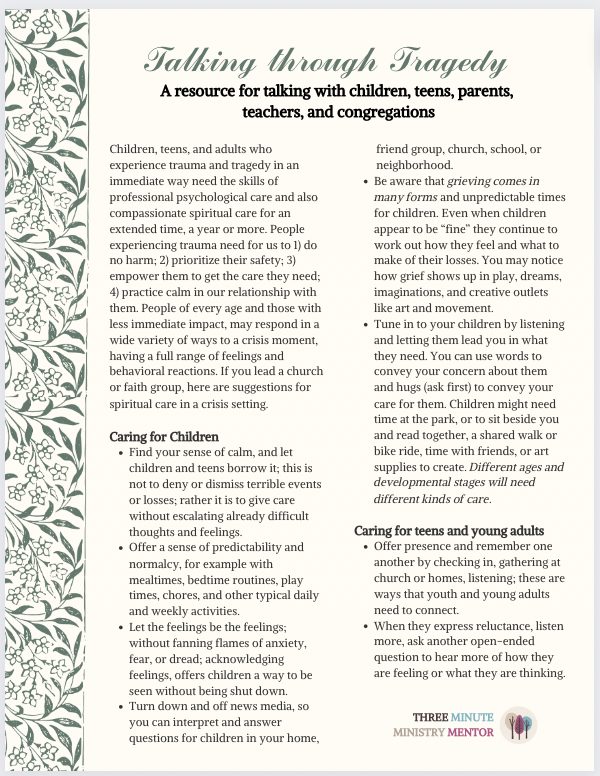

Talking through tragedy, creating sanctuary in a crisis, and accompanying people through ambiguous loss amounts to some of our hardest relational work in the practice of ministry. In this week’s episode I want to talk about all three forms of spiritual caregiving. We created a printable download (below). Please put it in your files. We want to help you be prepared for talking through tragedy and caring through crisis in your practice of ministry.

Talking through tragedy

How do we talk children through tragedy? What about parents and teachers, especially when the tragedy has impacted children and the places where children go, like schools or churches? And what about caring for congregations as a whole?

As you know, last week in Nashville, we experienced what is reaching epidemic proportions in the form of another school shooting. This time it was a private school on a church campus. There’s so much that could be said and needs to be said about this tragedy.

Let’s focus on how we care for our children when they are exposed to or become aware of the tragedies of our world. Closely related I want to talk about how we create a sanctuary in crisis for our people and the people of our neighborhoods, towns, and cities.

I’ve created a handout to put in your files. It is something you can take a look at when it comes time. I hope it never comes time in your town or city. And may we never have another school shooting ever. This kind of care, however, is certainly not limited to school shootings. Many other kinds of tragedy fill the news headlines and our social media feeds.

It would be ideal if our world was more focused on love and justice and making space for every human being to show up as themselves. And tragedies should be rare. But we know that this is not the case. So we need to be prepared to talk to our children and teenagers when crisis erupts. We need plans to help us respond with care and work for justice for our congregations and our wider communities.

Creating Sanctuary in a Crisis

One way to think about how we talk with one another is that with our words and with deliberate and fully present silence, we create a sanctuary in times of crisis.

How we frame the conversations about tragedy, crisis and loss makes a difference in how people feel supported and cared for through these hard experiences. When it comes to trauma and tragedy, or any crisis or loss, we can also use our physical space and the virtual spaces that we host to make sanctuary for one another.

In my congregation in Nashville, Tennessee we crafted an aspirational purpose statement. It includes these words, “We strive … to create sanctuary for one another with special concern for those who are marginalized.”

Several years ago while we were introducing and deliberating over the statement, this one particular phrase created possibly the most conversation. We are place at highly values equality, inclusion, and welcome. Some people felt strongly that creating sanctuary was something that was for everyone, all people, without distinction. On the other side of that conversation however we heard the intention and concern that some people socially experience marginalization in a more intense way. Sanctuary is needed more at times by some groups of people than others. We embraced both ideas in our statement.

In a crisis there are certain groups of people who need sanctuary in a very urgent way. We can create that sanctuary with a regular routines and habits of being together. We can also make sanctuary with the particular rituals of the church or faith group. Religious rituals like communion and singing, prayer and blessing, can help bound a sanctuary for people who are in emotional and spiritual pain and feeling lost. Activating these rituals can bring together communities for mutual care.

Accompanying people through ambiguous losses

Perhaps you wonder, why should anyone be emotionally activated by tragedy that didn’t cause a direct impact or loss in their lives?

There are a variety of reasons this may happen. Geographical proximity pushes away denial, showing us that tragedies can happened in our own neighborhoods and backyards.

It’s not just proximity, however, that activates people. A new crisis can bring into the present moment a person’s past experience of tragedy and loss.

Previous losses and tragedies, call forth big feelings that can overwhelm the emotional system and one’s sense of well-being.

The event does not even have to rise to the level of clinical trauma to give those seeing it or hearing about it a sense of repeating their own moment of crisis. We are easily flooded with powerful memories, big feelings, and dread at what may follow.

Even with no past crisis, our mirror neurons activate when we witness a crisis or trauma. And we may lose a sense of safety, security and belonging in that moment.

When we experience big feelings and hard stories, overwhelming concerns, they can fill up the spaces of our hearts and minds. We need to make room for them. Space to breathe. Room to think. Perhaps alone, or with supportive people. Big feelings, hard stories, and overwhelming circumstances need a witness.

These experiences tap into what Pauline Boss calls ambiguous loss.

First and foremost ambiguous loss results when someone is missing. A person in our lives can be physically absent yet emotionally and psychologically still present. For example in cases where a person goes missing, yet no body ever turns up. Or vice versa a person can be physically present yet not really with us for example in the case of Alzheimer’s or dementia. These are ambiguous losses.

The Loss of Children

My own theory, building on Pauline Boss’s concept, is that when we lose children to tragic death, to most any death even an expected one from a chronic or acute illness, and even if that child is not in our own immediate family, we experience a profound sense of loss because in our understanding children shouldn’t die before their elders. Children simply shouldn’t die but you live to adulthood. So in a way they’re present with us even after their deat creating an ambiguous loss that stretches beyond the immediate family or school or community. It’s culturally incomprehensible to us when children are killed by something as preventable as gun violence.

Circling back to the need for a witness… the work of accompaniment becomes an incredibly important task in the leaders of religious and faith based communities. People who experience ambiguous loss need help in naming it, understanding its power in their lives, acknowledging its truthfulness as an experience, and finding ways to live creatively with those losses. It’s not work to do alone. Accompaniment is what we can give to one another as we face are ambiguous losses.

Before Tragedy Strikes

The closer a tragedy is to your congregation, the more people it may activate, and the more crisis it may evoke for them. The closer it is to our circles of social support, the more overwhelmed we may feel. Neighbors and friends, and even people we urgently disagree with become profoundly human in this moment. When they face something like we have faced before, it can melt the barriers and disagreements between us.

If you are reading this, and thanking God that a mass casualty has not come to your town or city, now is the time to put relationships, care, and response training in place. Pastoral care in the moment of a tragedy is much better when there is a sense of readiness. We are never truly ready for an unexpected tragedy or crisis. But there are things we can do and systems we can put in place so that if needed we have resources to call on.

If you are reading this, and thanking God that a mass casualty has not come to your town or city, now is the time to put relationships, care, and response training in place. Pastoral care in the moment of a tragedy is much better when there is a sense of readiness. We are never truly ready for an unexpected tragedy or crisis. But there are things we can do and systems we can put in place so that if needed we have resources to call on.

When we need to talk our children youth and adults through tragedy we have some words we’ve already thought about. When we need to make sanctuary we’ve already thought about what rituals and what actions we can take in the moment to draw a sanctuary and allow and invite people into that space to make room for their big feelings and for the stories of what is unfolding. And when we need to be an accompaniment to those experiencing ambiguous loss we have given and thought we have a way to understand this very elusive kind of loss that impacts us when children die in such tragic circumstances when other tragedies strike our communities.

We are living in a new era of ministry. We need to talk about it and explore how to live into the new season with creativity, grace, and pastoral imagination. This three-session guide will help you lead these conversations with your Sunday School class, weekly prayer or study group, or leadership retreat. Read on to learn more and pre-order today!

Pre-order this week to also receive two bonus downloads!

Ways to thank pastors and ministers who led us through the last three years! And ways to expand your self care! Special bonus for everyone who pre-orders the #PandemicPastoring Study Guide.